What is PIALA

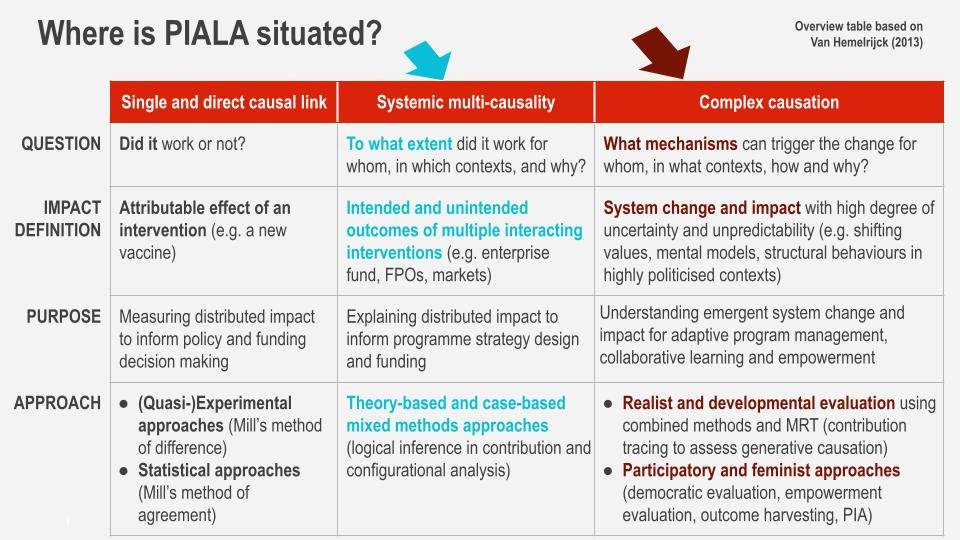

PIALA stands for ‘Participatory Impact Assessment & Learning Approach’ and is a theory-based, mixed-methods approach for designing and implementing evaluations and evaluative learning and research frameworks focused on assessing contribution to system change and impact.

Rooted in the realist, developmental, and transformative/feminist research and evaluation traditions, PIALA seeks to foster shared understanding and learning about how multiple interventions and influences interact to generate system change and impact. It provides a tested framework for creatively combining different types of methods and data (quant & qual, survey & dialogue, story & feedback, insight & foresight, Indigenous & Western) into an integrated ‘mixed design’ that is essentially systemic, participatory, and utilisation-focused.

PIALA Use Cases

PIALA provides leaders pursuing systemic change in challenging environments with a framework to adaptively manage and assess their strategies, portfolios, programmes, and projects. In highly complex contexts where numerous and often unpredictable interactions and influences make it impossible to isolate and control change, the framework enables strategic decision-making that reduces risk, based on credible evidence.

By combining performance and contribution analysis with Strategic Foresight, PIALA extends the horizon to assess the (likely) sustainability of emerging and envisioned impact in relation to both present and future variables, generating critical insights for strategic prioritisation and decision-making.

PIALA has been used in global institutional strategy and portfolio reviews, programme and project evaluations, and MEL and results framework design.

It was orginally developed and piloted with IFAD to address the main challenges of complexity in impact evaluation, namely:

The methodological challenge:

How to ensure rigour in assessing causality or causation in complex environments where there are no direct causal relations.

The validity challenge:

How to avoid ‘bias’ or ‘dominance of a single truth’ in value judgements of impact in complex environments.The utilisation challenge:

How to generate optimal shared value for various stakeholders and various purposes in complex environments.

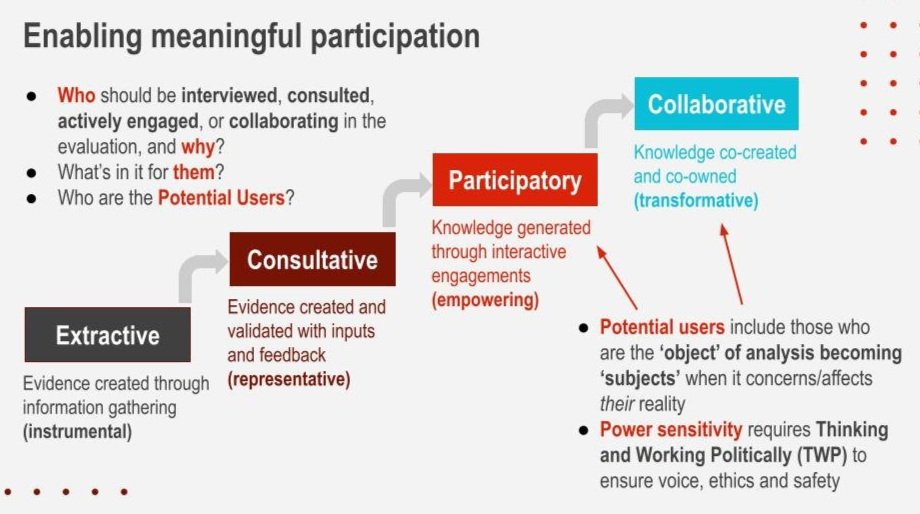

Pluralism and Meaningful Participation

PIALA pioneered Robert Chambers’ concept of inclusive rigour and builds on the premise that rigour, validity, and utility in evaluative research are enhanced when methods and processes are thoughtfully designed and combined to incorporate multiple views, values, realities, and knowledge systems.

Pluralism helps decolonise research and evaluation practice by challenging the dominance and imposition of Western knowledge assumptions that perpetuate failing aid.

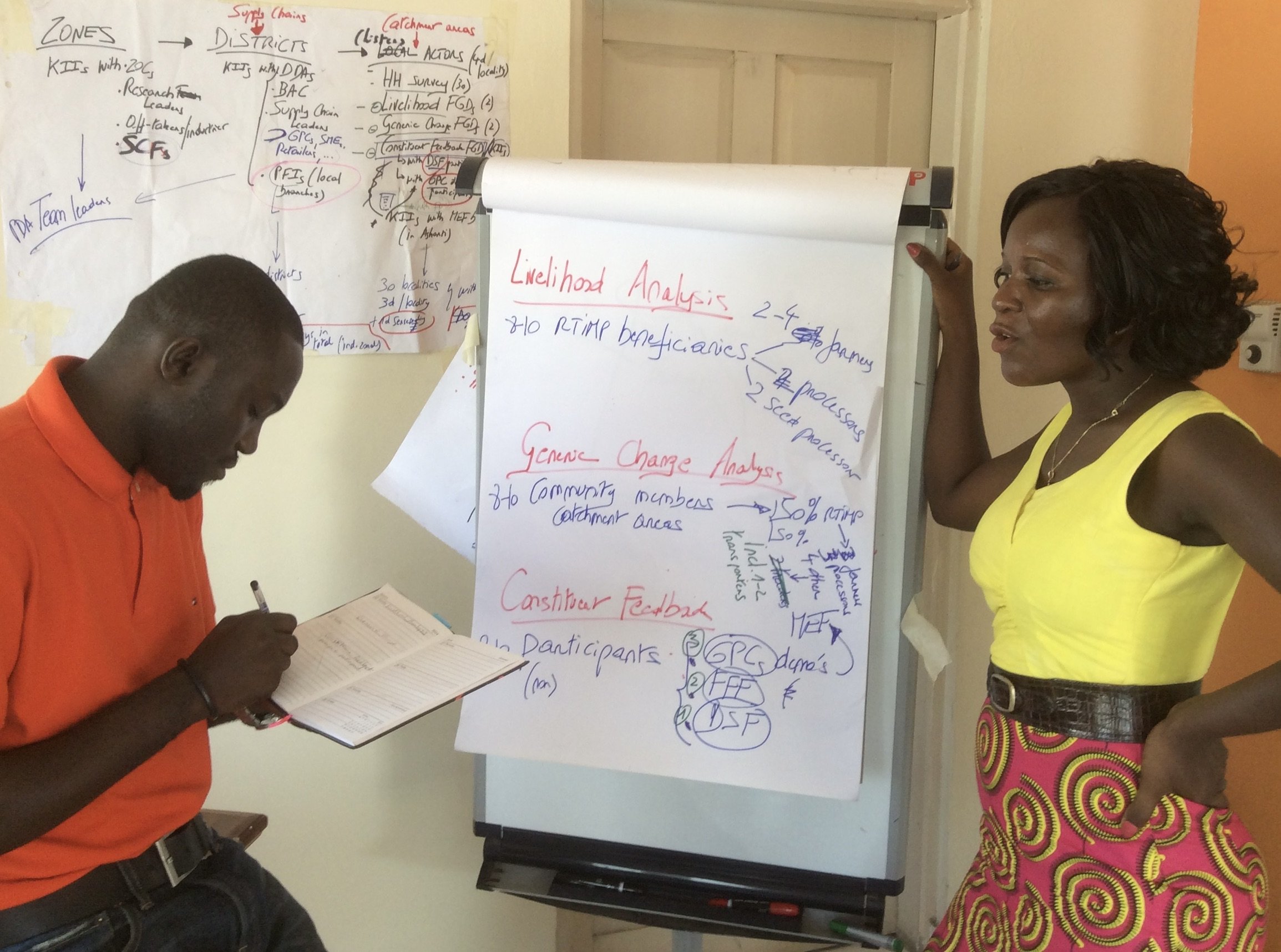

This calls for methods and processes that enable meaningful, non-extractive participation, taking into account participants’ resources and capabilities to engage and the power dynamics that shape their participation space. Participatory methods are adapted to local contexts and cultures, drawing on local forms of dialogue and knowledge while remaining cognizant of local politics and power dynamics.

Evaluating Systemically

PIALA rigorously assesses system change and impact across a broader portfolio through: (a) multi-stage sampling of and within ‘embedded systems’ (e.g. commodity supply chain systems, or local WASH governance systems); (b) within-case analysis against an evaluative Theory of System Change in each sampled system; and (c) cross-case comparison across all sampled systems.

It combines two complementary system change models that reinforce each other to reach the tipping point of no return where changes sustain and transform the systems and their wider ecosystems.

The Iceberg Model — Focused on achieving depth of change through changes in values, beliefs, and mental models, and assessed through PIALA’s within-case analysis of the ‘systemic-ness’ of these changes that drive stakeholders’ behaviours and interactions within each system.

The Diffusion Model — Focused on achieving breadth of change through innovation-driven behavioural shifts at a large sale, and assessed through PIALA’s cross-case comparison of change patterns and impact distributions across all sampled systems.

The PIALA framework

PIALA helps combine and adapt methods and processes for integrated data gathering and analysis by drawing on:

Two design principles:

Evaluating systemically, and enabling meaningful participation.Three quality standards:

Rigour, Inclusiveness, and Feasibility.Five methodological elements:

1. Theory of System Change;

2. Multi-stage sampling of/within embedded systems;

3. Participatory mixed-methods using locally relevant tools;

4. Participatory Sensemaking; and

5. Contribution Tracing and Configurational Analysis for within- and cross-case analysis.Ten co-design sliders:

Covering scope, scale, participation, causal analysis, methods, processes, data integration, and sensemaking.

Participatory mixed-methods

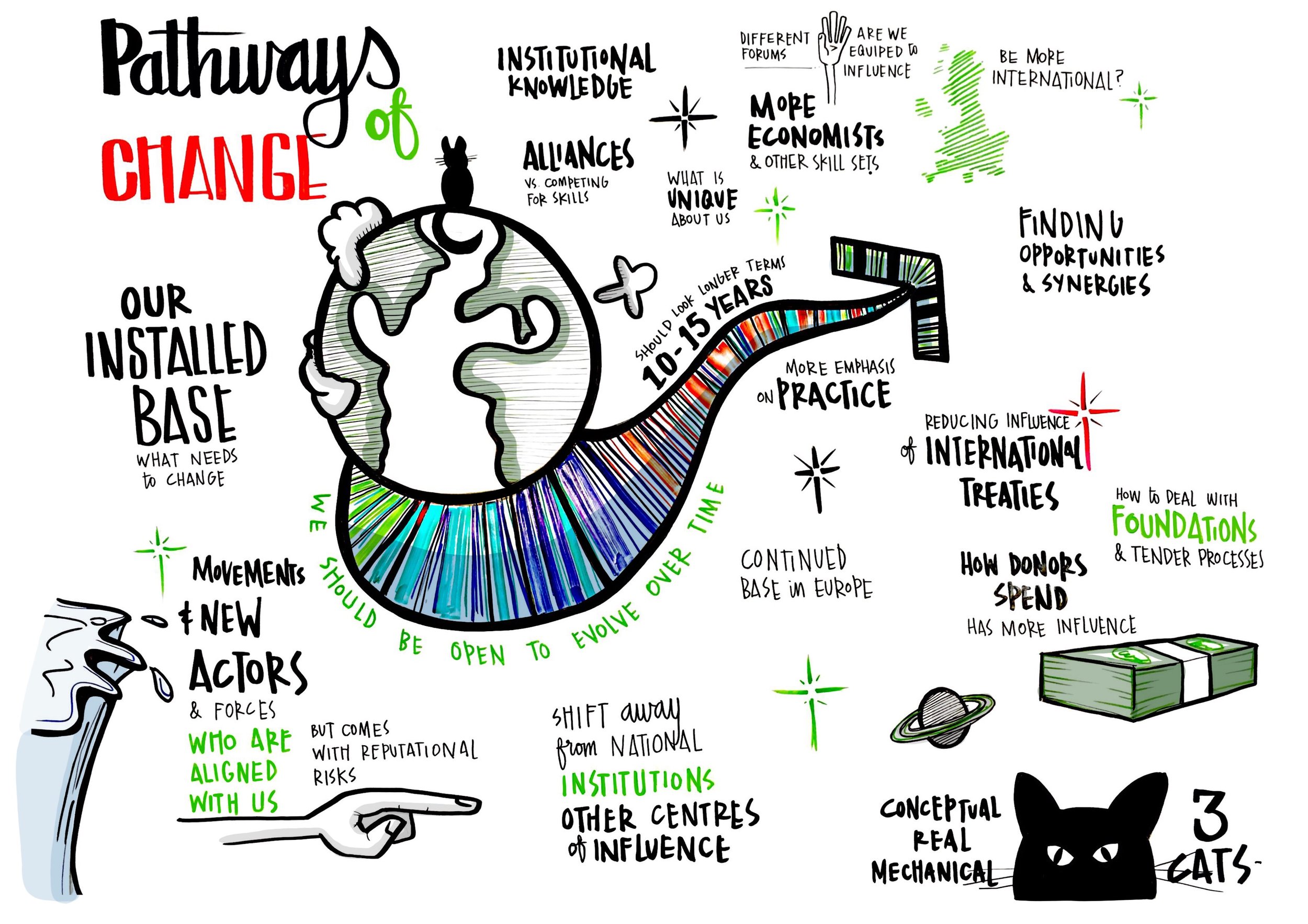

In a PIALA-based mixed design, methods are chosen to complement and analytically build upon one another, while also overlapping to allow for systematic cross-checking. They are chosen to probe for evidence and explanations of planned as well as emerging changes, accounting for both predictable and unpredictable influences and risks, while facilitating the discovery of unknown pathways.

Depending on the evaluation purposes/uses, scope, scale, and requirements, a PIALA-based mixed design may include:

Methods generating quantified qualitative data that can be subjected to statistical analysis if collected at a large-enough scale —e.g. Mixed-Surveys, Social Network & System Mapping, Constituent Voice, Participatory Statistics, and SenseMaker.

Methods generating more in-depth systemic explanations of observed changes through mixed and group-based inquiry and dialogue in a multi-case study design — e.g. Outcome Harvesting, Sustainable Return on Investment, PhotoVoice, Feminist and Indigenous Dialogues, and Participatory Sensemaking. Also Constituent Voice and Participatory Statistics apply group-based dialogue and analysis tools that generate systemic explanations.